“That year Lizzie’s kid sister kept a list of things that were funny when they happened to other people: tarring and feathering, Peeping Toms, mad cow disease.” Like the list that opens Einstein’s Beach House, the synopses of the eight stories that make up Jacob M. Appel’s collection are humorous from a distance — a couple adopts a depressed hedgehog; a former ventriloquist helps his girlfriend kidnap a tortoise from her ex-husband’s house; a woman has an affair with the father of her daughter’s imaginary friend — but become more insidious up close. In the title story, for instance, after a tourist guidebook incorrectly lists his family home as the former beach house of Albert Einstein, Bryce Scragg cleans it up a bit, decorates with a blackboard of equations and a fetal pig in a jar, and begins offering tours of the cottage — for a twenty-five dollar fee — much to the chagrin of his wife and the amusement of his daughters (the eldest of whom narrates the story). When a tourist inquires as to how they came to own the cottage — which Natalie, the narrator, informs the reader has been in her family for four generations — her father says that he bought it from Einstein’s niece. The goofiness of Bryce’s get-rich-quick scheme soon takes a chilling turn, however, when an older woman knocks on their door claiming to be Einstein’s niece and sole heir, forcing the family to vacate their home and to question the things they thought they knew about their lives and their place in the world.

These tales of domestic oddities demonstrate an instinct for withholding rather than the sensationalization so common in contemporary works vying for the attentions of distracted readers. It is always clear how Appel’s pieces could be taken farther. Einstein’s “niece” could continue to haunt the family, as opposed to being regulated to the status of a peculiar, never-again-spoken-of event. Or, in “Hue and Cry,” which follows thirteen-year-old Lizzie and her best friend/crush Julia as they spy on a sex offender who recently moved into the neighbourhood, the perversity, in another writer’s hands, would likely be made explicit. Instead, Appel allows his stories to play out with subtlety. As such, this collection may come across as understated to some readers. The prose isn’t particularly poetic or colourful, and it lacks the urgent uniqueness that some readers, like myself, look for in a novel or story collection. The use of clichéd phrases throughout the collection — “I regretted the words as soon as they left my tongue” and “I’m not sure what finally drove me to the edge,” for example — is also off-putting, as it takes the reader out of the story. Further, there is a lack of variation, though it is difficult to pin-point. The narrative point-of-view does change from piece to piece — sometimes first person, sometimes third; sometimes male, sometimes female; young, old — but the contexts of the perspectives do not vary widely. Certainly some pieces are more absurd than others (or their characters are more open to experiencing absurdity), but there is a persistent domestic quality that the stories and their characters cannot seem to escape. It is not quite a suburban environment, simply a restrained one. The third story, “Strings,” which follows a rabbi whose ex-boyfriend requests to borrow her pulpit for a concert of 400 cellos, concludes with the sentence “she wrapped her arms around his chest … secure in the knowledge that life’s greatest triumphs and calamities were safely behind her.” This closed-off ending, all wrapped up with a bow, so to speak, leaves the reader without any curiosity as to how the characters’ lives might continue beyond the story.

The majority of the pieces focus on familial units and the concept of home. This thematic consistency creates cohesion within the collection, but I also found myself hoping for at least one story with more of a sideways approach. What is interesting is that some of the characters are aware of this domesticality. The narrator of “The Shared Hostage” tries to nudge the ‘hostage’ towards a life of freedom while still acknowledging his own inability to reach complete freedom and honesty with his girlfriend. Leslie in “Paracosmos” may or may not be imagining that she is in an adulterous relationship, not so much breaking the monotony of her stay-at-home-mom existence as living out the possibilities of unreality extant within a domestic sphere. Appel doesn’t appear to aim for bigness, for a summary of all of human nature, which is simultaneously the collection’s strength and weakness. The collection misses an expansive quality, the moment when a story opens up and reveals something, not necessarily something life changing, but something that changes the reader if only for a moment; tints their metaphorical vision. Particularly in the first three pieces (“Hue and Cry,” “La Tristesse Des Hérissons,” and “Strings”), the restraint of the language creates a feeling of confinement and stasis. At the same time, there are many other contemporary works that attempt to achieve expansive moments, but only succeed in trying too hard. Appel never does this; his stories never try too hard to be what they are not. In “The Rod of Asclepius,” “Paracosmos,” and the title story especially there is never a sense of falsification. There are no blockbuster shocks or surprises or convoluted plots, yet the stories still manage to resist predictability. Some may say, “no risk, no reward.” But patience and withholding can bring their own reward. Appel mixes his instinct to withhold with the everyday absurdity of life to create generally successful stories of forgiveness and the ongoing tensions of the passage of time, of knowing and not knowing and of wanting to know but ultimately being unable to know.

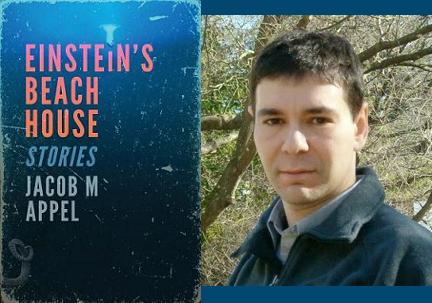

Appel, Jacob M. Einstein’s Beach House: Stories. Pressgang, 2014. 179 pages.

ERIN DELLA MATTIA is a writer, researcher, and almost-graduate of Ryerson University’s Literatures of Modernity MA program. Her work has appeared on Rookie Mag and The Word on the Street Blog, among other places, and her creative essay “Zine Culture and the Embodied Community of Rookie Mag” was published as part of Ryerson’s Stories in Play Initiative earlier this year.