Little Black Afro Theatre Company returns with a revised version of Carbon, originally performed at the 2014 Hamilton Fringe Festival.

Carbon’s basic unit is the set piece. There are sixteen of them; each built around a different spoken word poem, each poem as much a character study as a stand-alone narrative. Instead of a traditional plot, audiences get to choose the order of the pieces. Carbon’s structure is capably left to a few shared themes — love, growing up, we are all made of stars — and the uncanny similarities that arise from people talking courageously about who they are. Also to the blocking and set design, which treat architecture as poetry in space. The angles and shapes created with simple rope, a sheet and a modified bookcase echo with symbolism.

In “Cooking with Cass,” Cass Brennan (pictured above) is a brilliant comic mess as she assembles her take on a mud pie. Her delivery is tailored to the present moment, vibrant with anxiety at the uncertainty of whether or not we’ll enjoy it, but also confident enough in what she’s doing to not be swayed by our opinions. Hers is a heart-racing immediacy.

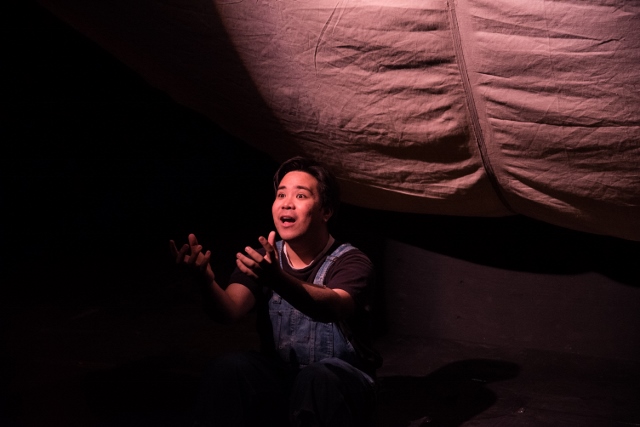

The same goes for Charles Diokno Manzo, who is aglow as an enamoured patient in “My Blonde Paramedic.” He feels out his character like D’Angelo does a groove: with no rush and no worries about acting a fool. He and Brennan, who plays the paramedic, make room to pay attention to each other and enjoy it without once telling us how to feel.

Charles Diokno Manzo. Photo by William Cook.

Kano Wilkinson’s “Puberty” is what Emily Dickinson meant when she said her business was circumference, to lasso the supposedly unrelated together and show otherwise. In this case, it’s the audience. Using the word “puberty” as an acronym, Wilkinson recites variations of it like the words of a favourite song, like he knows us well enough to know our favourite songs. The acronyms’ ridiculous truth — “People Understand Boobs/Boners Erase Real Thoughts, Yearly,” for example — is more than enough enticement to meet him halfway.

Aaron Robertson, Stephanie Gundert and Kano Wilkinson. Photo by Cesar Ghisilieri.

The show’s producer, Luke Reece, briefly introduces poems with musings on the theatre and behind-the-scenes anecdotes about Carbon’s inception. He apologizes a lot for not knowing what to say, so often that his mere presence becomes an act of absurdity. He embodies the feeling of saying a word over and over, the kind of palate cleanser Beckett might have written if so compelled. The rest of the players bully Luke when he speaks and play the foil, cleansing themselves through aggression.

Carbon carries itself because nobody hides behind it; rather, actors coax the work out into the open by getting their intellects out of the way. There is no sense that Little Black Afro is doing something with the performance. It’s just humans making sense of their condition through verse by letting us see if we recognize ourselves in it, and assuming responsibility for it by forgoing backstage breathers to ready the set. A humble twist on the empowering self-affirmation often associated with spoken word.

Luke Reece. Photo by William Cook.

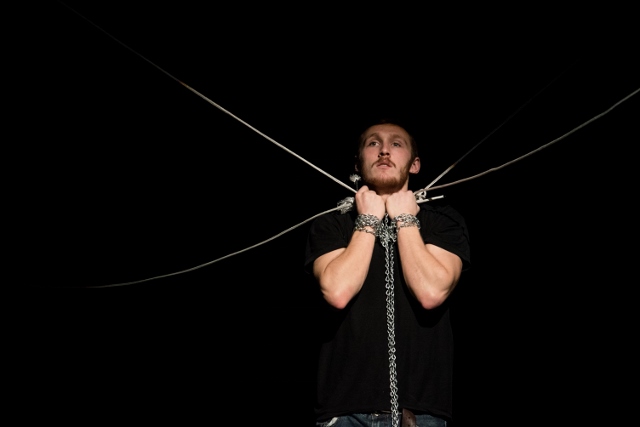

The night ended with Aaron’s Robertson’s “A Girl and A Door,” easily Carbon’s most compelling visual arrangement. Robertson chains his hands to four pulleys above the stage and yearns for human connection in the industrialized city. He does a good manic preacher, ever boisterous but at heart unsure whether life is serendipity or meant to be. Praise Lady Fortune and the bones her wheel occasionally throws us.

Aaron Robertson. Photo by William Cook.

Carbon is a welcomed addition to Toronto spoken word, where most are reverent to Button Poetry’s whims and the prevailing knowledge is to captivate people by shaming them into agreement. With few exceptions, it’s eighty minutes of sustained appreciation for audience and craft and is truly regenerating.

Little Black Afro’s latest runs March 16-19 at the Aki Studio Theatre (585 Dundas St. East).

Buy tickets here.

Ten percent of box office earnings will support Louder Than a Bomb Canada, the biggest youth poetry festival in the country.

Photo by Sandro Pehar Photography.

Trevor Abes is a poet and arts writer living in Toronto, Canada. He was part of the winning ensemble at the 2015 SLAMtario Spoken Word Festival, and competed at both the National Poetry Slam and the Canadian Festival of Spoken Word as part of the Toronto Poetry Slam team. His work has appeared in the Hart House Review, The Rusty Toque, Torontoist and untethered, among others. You can follow him on Twitter @TrevorAbes.